“We are talking now of summer evenings in Knoxville, Tennessee, in the time that I lived there so successfully disguised to myself as a child.”

A film reviewer died recently. Until disease silenced him, he was a ubiquitous presence, especially on public television. Upon his death, his numerous obits highlighted his work not only in film but in other forms of journalism, a script for a produced movie that he wrote, and his politics.

I was always disquieted by his dismissive and condescending attitude towards his television co-host, by the fact that the movie he wrote was smutty and superficial, and that his politics were disappointingly prosaic. However, his written work was remarkable for its genre, as he brought thoughtfulness to every movie review, even if the film were some slasher nonsense or Hollywood cluster bomb.

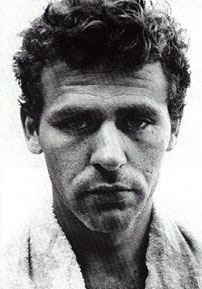

It is thought by many of the generations younger than my own that this purposeful and literate style of film review originated with the recently departed, but in fact it was a standard that was set by the "father" of American film critique, James Agee.

Agee originated the film review as we now know it while on the staff of Time/Life magazines in the 1930's and 40's. In his reviews, he would examine thematic structures, narrative flow, soundtrack recordings, camera angles, costumes, and the range and talents of the actors. With the same zeal applied by literary critics to their craft, Agee took film seriously enough to recognize it as a true American art form and and present it as such. Film directors Francois Truffaut and Martin Scorsese credit Agee as an inspiration for their subsequent work, which is especially interesting since both of those film-makers began their careers as reviewers.

In that light, appreciate this consideration of Agee as film critic that was offered by the National Endowment for the Humanities:

The Agee style—intensely literary and endlessly alert to the textual nuances of an emerging medium—was a striking departure from the prevailing movie coverage, which often seemed little more than a willing arm of the studio publicity mill..[his work] affirmed the stature of film criticism as its own art form, creating a standard that subsequent generations of reviewers have tried to match. Decades after Agee’s passing, the idea of film reviewing as something intellectually valuable seems thoroughly mainstream. But when Agee was making his way as a journalist in the 1930s and 1940s, few editors were interested in devoting “think pieces” to something so seemingly transient as a Hollywood flick. In fighting for film’s place in the pantheon of modern culture, Agee was defying convention, even at the risk of stalling his career.Were he only a critic, he would still have produced an admirable body of work, ably captured in a two-volume anthology entitled Agee on Film, used copies of which are still to be found. Included in this collection is his essay on silent film comedy that is still the best analysis of what made Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, and Agee's favorite, Charlie Chaplin, transcend their era and create the unique style of physical comedy that is still as prized as it is elusive in contemporary cinema.

However, like the recently deceased movie critic, Agee was also a screenwriter; albeit of a film of greater quality and endurance. In 1951, working with the director John Huston from a novel by C.S. Forester [the author of the "Horatio Hornblower" series], Agee wrote the script for "The African Queen", starring Humphrey Bogart and Katherine Hepburn. The film, now considered a classic, won Agee an Academy Award nomination for best screenplay.

But there's more: In the 1930's, Agee was commissioned by Fortune magazine to tour Alabama during the Great Depression with photographer Walker Evans. The photo essays, compiled into a book entitled Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, display through stark pictures and lush prose the realities of poverty in the United States. Fortune found this approach too experimental and the magazine did not publish the finished product; the general public did not warm to it, either, as the book originally sold very few copies. These days, it is considered a masterpiece in social commentary; a paradigm for all that followed.

So, highly literate and memorable film criticism, a pungent social commentary on poverty in the United States, an Oscar-nominated screenplay; any of these would have marked Agee as a member of the upper echelon of mid-century American writers. But, there's more....

At this point I should mention that, like many authors, Agee had a problem with alcohol; a rather great problem with it. So great that it would affect his health to such a degree that he would die in the back of a Manhattan taxi cab in 1955. He was 45 years old. What makes his death all the more remarkable is that it occurred on the anniversary of another death, that of his father; and that brings us to yet another arena of Agee's talent.

Although his father was fond of alcohol, too, it was an automobile accident in Knoxville that killed him. Agee was 9 years old at the time and the tragedy haunted him for the remainder of his life. So much so that he poured the grief that was not pickled in booze into a novel that he carefully crafted, like polishing a fine gemstone, for much of his adult life. The father he barely knew became a physically absent, but certainly powerful, character in A Death in the Family, the novel that was discovered among Agee's personal papers upon his death and that, upon publication in 1958, won the Pulitzer Prize in fiction.

Consider this oft quoted description of summer in Tennessee:

Supper was at six and was over by half past. There was still daylight, shining softly and with a tarnish, like the lining of a shell; and the carbon lamps lifted at the corners were on in the light, and the locusts were started, and the fire flies were out, and a few frogs were flopping in the dewy grass, by the time the fathers and the children came out.Like other writers we have examined on past Fridays, there is something compelling about sentences of that quality, whether in a novel, screenplay, film review, or photo caption.

As we live in a world where TV shows like Mad Men explore, in a ham-handed and pseudo-literate manner, the existential questions that have claimed the attention of mid-century Americans, a reading of any biography of James Agee would reveal a quest for identity far more compelling and less contrived than Don Draper reading Dante on a Hawaiian beach. This quest was found, as well, in his film and fiction characters and in the themes of the movies that he loved. It's a pity that he is so little regarded these days when lesser film reviewers, script writers, and novelists seem to be mining this rather fertile and familiar territory.

My own interest in Agee reaches back to my days as a literature grad student, when I used to delight in finding obscure, but worthy, writers and artists who had been all but forgotten. When I discovered Agee's novella about a student keeping the Maundy Thursday to Good Friday vigil at his Episcopal boarding school's chapel, well, I was hooked. There is always an undertone of Anglican spirituality in Agee's works, along with the themes of redemption and reconciliation that are recognizable to anyone who is, in the traditional sense of the word, devout.

A Death in the Family is now a Penguin Classic and still in print, as is Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. The Library of America has collected the best of Agee's film criticism in James Agee: Selected Film Criticism and Journalism and another volume that features Death, Famous Men, and the aforementioned story of the vigil, The Morning Watch. All may be found through online book dealers or even in one of the rare physical bookstores that offer classics in American writing.

For a more personal experience, please read or re-read my reminiscence of a few months ago in the The Coracle of Evening Prayer with Father James Harold Flye, who had been Agee's school chaplain, mentor, and friend. The dualism of Agee's twin mentors, the pious and kind Flye and the roisterer John Huston, also would mark the interesting dichotomy present in his creative process. Maybe someone will make a TV show or, better yet, a film of it one day.

[Originally published on April 12, 2013]