Earlier this week, some British soldiers' remains, newly discovered, were finally interred after a proper reading of the Episcopal/Anglican Burial Office, nearly a century after their deaths. It caused me to recall a number of British soldiers who were famous among boys and young men during my formative years, especially those years spent in the UK. While it is no longer fashionable to think so among the NPR/NYT crowd that shapes common opinion, outside of that shrinking bubble there are still those of us who find the warriors worthy of some admiration. If you find this an odd statement for a clergyperson to make, I will assume it's because history wasn't your favorite subject. Yet, in the aftermath of yet another terrorist attack, there is something of their resolve that all of us may need to adopt to fulfill the evolving expectations of citizenship. After all, and as a number of international news outlets noted, it is an American tendency to run towards the site of disaster to offer aid rather than away from it in panic.

I can't remember where I read it, as it was in the middle of an Internet surfing expedition, but it was in an article about the personality types that tend to excel in periods of emergency. During peacetime or times of social harmony, these types either tend to be querulous, difficult in their interpersonal relations, and display a profound tendency towards addictive disorder; or they are shy, retiring, and largely all but socially invisible. In war or natural disaster, they are irreplaceable, as their leadership and ability to claim immediate authority often means the difference between survival and death or victory and defeat.

An infantry officer of my acquaintance [that's one way of putting it], a Marine Corps captain, used to call it the "Woody Allen syndrome". The guy who was least likely to serve any logical purpose in a tactical unit, who did not apparently fit either intellectually or physically into any command structure, would transform in times of extremis into an absolute fire-eater.

Two such fellows came to mind as I was reading the article. During times of peace, one found himself socially listless or in conflict with authority, disadvantaged by drink, or...um...challenged by conventional norms of moral comportment. The other merely a good, quiet Scot of an apparently benign and affable mien. Both were the kind of men who were lofted up in post-war British society as examples of moral and physical courage; men worth emulating in general character.

Robert Crisp was a cricketer of some renown from South Africa and holds a record that still stands in professional cricket [more than once he had taken four wickets in four balls as a bowler; I have no idea what that means but it always impresses the heck out of cricket fans]. He was also famous for his womanizing [Is that still a term we can use?] and drinking. Unable to contain his general exuberance, he also climbed Mount Kilimanjaro twice and swam the length of Loch Lomond in Scotland [Having swum the Loch myself, all I can say is “ew”; it was not the cleanest body of freshwater].

He just looks like the kind of guy you don't want taking your daughter on a date.

Despite his accomplishments, or perhaps because of them, Crisp was in near constant conflict with authority. So, naturally, he became an officer in the British Army, immersing himself in a command structure where he often ran afoul of senior officers, being either promoted for original thinking, demoted for general insouciance, re-promoted for battlefield innovation, and re-demoted for inappropriate behavior time and again. When not engaged in this funicular of military service, in addition to being near-mortally wounded several times, Crisp created a tactic for engaging, with his underpowered and under-armored tank squadron, the superior tanks of the German Army and routing them.

It's hard to believe, but there are actually ten clowns inside of that thing.

On one particular occasion, Crisp charged a line of Field Marshal Rommel’s best and, with one medium-sized American-made tank, successfully stopped 70 heavy-duty panzers. He would end the war as a major and be awarded, among other medals, the Distinguished Service Order. He then found himself unemployed.

Never to be daunted, Crisp continued his life of adventure, first writing two well-received books about tank warfare, one of which was still being read in military training courses in the US as of the mid-1970’s, and becoming a travel writer/journalist of some popularity. When diagnosed with cancer in late middle-age, Crisp engaged in his own form of physical therapy by hiking around the island of Crete. His cancer went into remission. He would spend the end of his life living in a beach hovel in Greece, in the evenings entertaining a rather broad range of women, both local and tourist.

He died in his sleep at the age of 82. An entertaining article about him may be found here. His books about the war in Greece, The Gods Were Neutral, and the war in North Africa, Brazen Chariots, are still in print and also now available in electronic editions. I can't say they are of general interest in our rather beta culture, but they are worth reading for anyone interested in 20th century history.

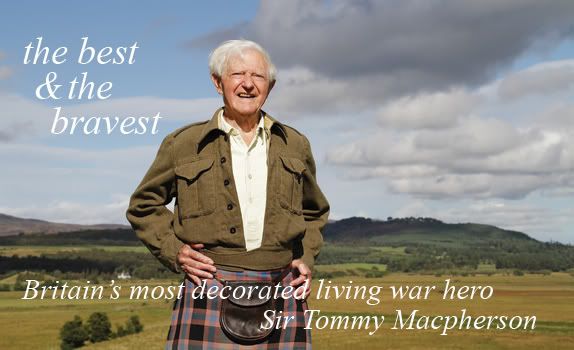

Tommy MacPherson was never a roue of any sort, certainly not of the Crisp quality; however, like the cricketer, he was one of those people one would not have expected to be anything more than a typical landowner’s son and clergyman’s grandson.

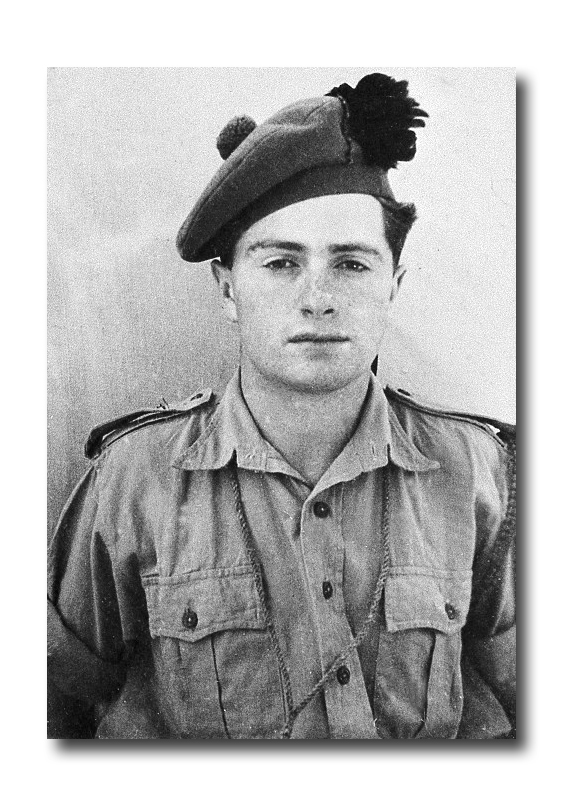

Any war can be improved by wearing a jaunty hat

MacPherson, a Scot, and I share an educational institution, as he is one of the stellar alumni of Edinburgh Academy, and it is there that I first heard of him. While Crisp was often featured in the ripping yarns of mid-century British boys’ magazines, MacPherson was a quieter sort, at least in terms of self-promotion, not of deeds.

After a rather ordinary early life for one of his social class, MacPherson joined the Royal Army at the beginning of World War II after earning degrees at Oxford in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics and representing his college in rugby. He was initially commissioned a subaltern [what US forces call a “second lieutenant”] with one of the Highland regiments. Shortly thereafter, he was transferred into the notorious Number 11 Commando, a unit made up of the maddest of mad Scots, and it is here that he earned his reputation.

In his first mission, MacPherson and three others were sent to recon the beaches of North Africa in a couple of canvas kayaks. They leaked and the submarine that was to meet them never showed up. So, they decided to land and walk to Tobruk, which was a mere five days away, somewhat complicated by the fact that the four-man team had no food or water and was clad only in swim shorts. Pathetically, they were captured by...yes, the Italians.

MacPherson made at least three failed escape attempts. When the Italians turned over their prisoners to the Germans, he made another couple of escape attempts. When the prisoners were transferred to Austria, MacPherson escaped again, was caught again, was transferred into Poland, and escaped again. This time, he was successful.

Upon his return to the UK he was awarded the Military Cross and invited to return to occupied Europe to create general chaos on behalf of the Allies. Of course, he said “yes”. Scots.

In advance of D-Day, MacPherson parachuted into France to fulfill the direct orders of Winston Churchill to, in the PM’s words, “set Europe ablaze”. Winnie had a way with words, without question. Since he had so much experience with being captured, and since he didn't wish to be executed as a spy, MacPherson decided to operate as a secret agent in Nazi-occupied France while dressed in the full service uniform of an officer in the Highland Regiments, including tartan kilt and argyle socks. From a distance, it looked to members of the French resistance that someone had brought his wife with him on a mission.

Hey, James Bond never had to wear a skirt.

Thus attired, and equipped with a resolute, if factually vague, mission from Churchill himself, MacPherson committed to a program of active mayhem across the French countryside. I could list, with viscera, the details of MacPherson’s actions, but it will suffice to note that during this time he earned the nickname “The Kilted Killer”.

I will offer this anecdote, however:

“On another occasion Macpherson took decisive action as the Second Motorised SS Infantry Division and the Das Reich Division pushed towards the fragile Normandy beach-head. Unarmed and accompanied by a doctor and a French officer, he drove a stolen German Red Cross Land Rover through ten miles of enemy-held territory, through machine gun fire and straight to the Das Reich Division headquarters where, dressed in full Highland regalia, he warned that he would unleash heavy artillery and call on the RAF if they did not surrender. In consequence, 23,000 German troops surrendered. It was a bluff that may have saved thousands of lives.”

After messing up France, MacPherson was sent to Italy to generally harass the remaining members of the German army. He did so with relish and, by war's end, was Britain's most decorated soldier. He stayed with the so-called Territorial Army of the RA for the remainder of his military career, retiring as a full colonel. He is still alive and very well. In fact, Sir Tommy, as he is now known, still makes an annual visit to his alma mater in Edinburgh to the delight of the students and the vexation of the more pacifistic members of the faculty. "Scots wha hae!", Sir Tommy.

A few years ago he published his autobiography, Behind Enemy Lines. It's on my nightstand, about three books down, but like its subject, I may give it a promotion.