"I'm a painter, not an artist".

I always wanted to write a biography of Waldo Peirce, mainly because of two photographs, separated by about twenty years. The first is of Peirce with his Harvard roommate; the second of Peirce with a writer friend on a beach in France in the 1920's. There is nothing remarkable about either photograph, except that his college roommate would become one of the most influential and famous journalists of the early 20th century and his beach buddy would win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

There is much about Peirce that I really shouldn't care for, as he was born into money, had a first-class education shoved into his grudging hands, and was able to move easily through the seminal experiences of the American century, dragging along four wives, five children, and a considerable number of paintings. It all came to him rather easily, along with rude health and vigor. He once stated that he never worked a day in his life.

But, what's interesting about him is that he was what Goethe and Balzac referred to in their respective languages as a "life-artist". As we have seen before with literary artists such as Yukio Mishima and James Magner, there is something compelling about those who wish not only to create tactile art, but to merge their lives with it so that it is a seamless expression of the sheer joy of living out of the bounds of normal expectation.

Peirce was sent to Phillips Andover and then to Harvard where his roommate was John Reed, eventual author of Ten Days That Shook The World, who was a great chronicler of the worker's movement in the United States and of the Russian Revolution. So prized was Reed's sympathetic reporting during Lenin's rise to power that he is buried in the Kremlin Wall. [Some may recall a film of thirty years back entitled "Reds", which starred Warren Beatty as Reed]. Reed and Peirce took a trip to Europe upon graduation and got into some trouble with the shipping line on the return voyage. Peirce, upon leaving port, decided that the ship and its accommodations weren't to his liking so he jumped overboard and swam back to shore. Upon discovering a missing passenger, the ship's captain had Reed locked in the brig under suspicion of murder. There are a number of endings to this story, the most amusing is that Peirce was waiting at the dock upon Reed's arrival back in the United States, having taken a faster ship, thus untangling the potential murder charges.

During World War I, like other men who would one day claim distinction in the art world [a full list may be found here], Peirce joined the Red Cross Ambulance Corps and served with distinction at the front, gaining some French medals along the way. After the war, and again like many Americans who served, he remained in Paris to be a part of the very large and creative expatriate community that included Ernest Hemingway, who became one of Peirce's life-long friends.

From a Harvard Magazine article from some years back:

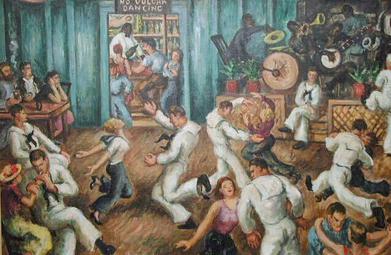

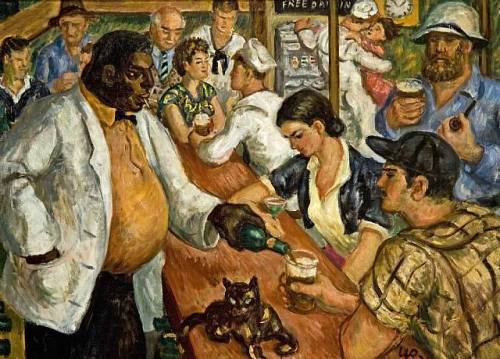

Living and painting in Paris off and on in the 1920s, Peirce became friends with many of the notables who defined this period in the arts: Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, Sylvia Beach, Bernice Abbott, Archibald MacLeish, LL.B. ’19, John Dos Passos ’16—and Ernest Hemingway, another wartime ambulance driver. He and Hemingway stayed friends for life, a relationship not sustained by many other Hemingway associates from the Paris days; their letters to each other were filled with news, gossip, and witty passages, often interlaced with Spanish and French asides. Both men were voracious readers. Both were remarkable presences in a room, regaling others with ribald tales, great stories, and vivid word pictures. Their six-foot frames and beards were as impressive as their artistic talents. (Peirce was occasionally referred to as the “Hemingway of American painting,” but said once that made as much sense as “calling Hemingway ‘the Peirce of American literature.’”) Both men shared a formidable gusto for life and adventure—each married four times—and possessed an unending, consuming curiosity about the world around them. Fishing was their passion, and several times Peirce joined Hemingway in the Dry Tortugas and the Marquesas Keys. Never without a sketchbook, he captured these expeditions in oils and watercolors. When Hemingway’s face graced the cover of Time in 1937—he had just published To Have and Have Not—the magazine used a Peirce portrait of his friend holding a fishing pole, eyes focused on the line. The two can also be found together in other Peirce paintings—fighting bulls in Pamplona, drinking in Sloppy Joe’s in Key West, catching tarpon in the Gulf Stream.On his many visits to Key West, Peirce was always sure to bring both his paints and his children, along with a rather singular sense of the duties of fatherhood. Hemingway wrote in a letter:

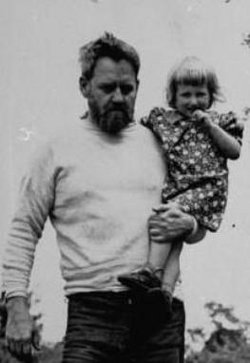

"Waldo is here with his kids like untrained hyenas and him as domesticated as a cow. Lives only for the children and with the time he puts on them they should have good manners and be well trained but instead they never obey, destroy everything, don't even answer when spoken to, and he is like an old hen with a litter of apehyenas. I doubt if he will go out in the boat while he is here. Can't leave the children. They have a nurse and a housekeeper too, but he is only really happy when trying to paint with one setting fire to his beard and the other rubbing mashed potato into his canvasses. That represents fatherhood."

He lived a long life and left many works of art scattered about museums both great and small, including the Smithsonian. The bulk of his estate was left to Colby College in Maine, near where he lived his final two decades, including not only paintings but some of the most entertaining letters one can ever hope to read.