"I hereby declare myself another order of being. Will you give up your destiny?"

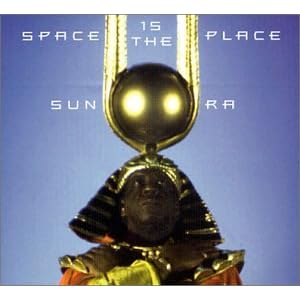

Legally, I was too young to be in a nightclub by about three years. I tended to take advantage of my older appearance to get into places where musicians I wanted to see were performing. Sometimes it would be to places like the Smiling Dog Saloon on Cleveland's West 25th St., where a sixty year old man dressed in gold lamé with a pharoah's headpiece was leaning over me, while he conga-lined across the floor, bidding me to repeat after him and declare myself another order of being.

I did so, if just to appease his intergalactic majesty, Sun Ra. Also, I was concerned that if I didn't go along, the bouncer would notice that I was only eighteen years old in a 21+ club.

Still, sneaking into a nightclub was a chance I was willing to take to see one of the most unique, if not the most unique, jazz composers, performers, and orchestra leaders of the 20th century.

Every performer needs his or her "hook", the gimmick that marks them as particular and causes them pleasantly to lodge in the memory and regard of the public. We all know, if we're old enough, that Jack Benny was cheap, that Rodney Dangerfield did not get no respect, and that Pete Townsend would bust his guitar on stage at the conclusion of a performance [oh, to have had that guitar repair contract]. Duke Ellington was elegant; Count Basie wore a yachting cap; Dizzy Gillespie's cheeks blew out like a puffer fish's.

Although Herman Poole Blount originally had no stage gimmick, he did have enough talent to play any type of jazz, even the kind that was heard only within his head. As a young man, he played piano with both jazz groups and rhythm and blues bands. He loved all kinds of music and was able to, after listening once to a musical selection, render it on paper in correctly transposed notation.

In the mid-1930's he formed his own band, The Sonny Blount Orchestra. They toured a lot of small towns and were critically acclaimed, which meant they were flat broke and out of business within a year. He then found a lot of work with all sorts of bands in Birmingham, Alabama; enough to keep him from starvation, anyway.

To understand Blount's transformation, one must have an appreciation for the particulars of Birmingham jazz. Each city has a style, of course, some are obvious and well-known: the raucous, joyful noise of Chicago, the jangly energy of Detroit, the earthiness of St. Louis, the low-down bluesy-ness of Memphis, the antique slide and jump of New Orleans. The jazz of Cleveland is always marked by the use of the organ. To this day, I cannot hear a Hammond B3 and not find my senses transported to Euclid Avenue at night.

Birmingham nightclubs favored the exotic in their stage design, with dramatic lighting and murals depicting scenes of far-away dreamscapes. The sound they produced was tight and big, with full orchestras inviting people, both black and white, to the dance floors. Because it was a small city, B-Town musicians saw themselves as a community, always well-dressed and, in public, well-behaved. Their camaraderie was obvious both in their mutual regard and in the remarkable music they produced. It was once said that one B-Town jazz man could read the mind of another, knowing when an extemporaneous key change was coming or whose turn it would be to offer the next solo without having to rely on any obvious form of intramural communication.

It was in this milieu that Blount really learned his craft; and it was in Birmingham that he had a moment of, well, let's just call it a form of interplanetary psycho-sacred epiphany. We'll let him describe it:

"… my whole body changed into something else. I could see through myself.... I wasn't in human form … I landed on a planet that I identified as Saturn … they teleported me and I was down on stage with them. They wanted to talk with me. They had one little antenna on each ear. A little antenna over each eye. They talked to me. They told me to stop [attending college] because there was going to be great trouble in schools … the world was going into complete chaos … I would speak [through music], and the world would listen. That's what they told me."

While it took a few years, and service in the US Army during WWII to realize, it appears that Sonny Blount never really returned from Saturn. He was replaced by Sun Ra, the persona and the name that he adopted in the early 1950's. Although they would bear various, albeit similar, names during the next forty years, from that time forward Sun Ra would always be the leader of his "Arkestra".

So it was in the winter of 1974 that I found myself, after discovering his music in the dusty back wall of the record library of the radio station where I served as a part-time, late night DJ, experiencing the magic and mystery of Sun Ra and his Intergalactic Space Arkestra. While some of it was truly weird, most of the music was a recognizable collision of bebop, Miles Davis-style laments, orchestral jazz, and improvisation on an early synthesizer. It was both classic and spacey at the same time. One moment, after one of Ra's jaunts around the room bidding us all to repeat after his bizarre intergalactic creed, and at the end of a particularly dis-harmonic moment of space jazz, without a word he and the Arkestra smoothly jumped into Ellington's "Take the A Train" and played it flawlessly. In fact, it may have been the best live version I've ever heard.

Sun Ra died in 1993. No one was really sure of his age as he was always secretive about his past, but he was believed to have been around 75. He left a very large fan base, as one might expect from a cult music figure, but was also a great influence to some of the more flamboyant of the funk and hip-hop acts that would mark the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Why use words when we can use music, though: