There was a time when archaeology was more an avocational pursuit by wealthy adventurers and treasure-seekers than a branch of anthropological and scientific inquiry. In fact, the earliest techniques adopted by archaeologists were the same used by the tomb-robbers who had vexed every important site, whether a burial place or ancient structure, from Egypt to the Hebrides since before anyone bothered to record such occurrences. One of the great frustrations to Egyptologists is that every single pharaoh's tomb, save for the rather small and poor one of Tutankhamen, was robbed within a year of a pharaoh's committal.

Obviously, such a state could not be allowed to exist as, between the larceny of tomb-robbers and the avariciousness of well-connected hobbyists, many of the world's great treasures were being stolen, lost, destroyed or otherwise mishandled. Heroically, and using the power that came with being British subjects at the height of imperial power, the faculty and staff of some of the colleges and institutions at both Oxford and Cambridge Universities, chiefly those from the Ashmolean Museum, dedicated themselves, their influence, political power, and academic training, to reversing this trend. There are many great personalities that were involved in nudging archaeology into its proper place in the pursuit of human history, but one seems to stand out not only for her academic rigor and her willingness to lead in the field, but also for her resistance to pressures that would have disrupted the objective purity of her discipline.

Kathleen Kenyon was born in the early part of the 20th century; her father was the director of the British Museum and a renowned scholar of the Bible. She was a powerful scholar herself, graduating from Somerville College, one of the women's colleges of Oxford University, with a degree in history. I sometimes try to imagine what it would be like to be a child and to have complete access to the wonders of a world-class museum, to have free reign to wander through its halls and exhibits whenever you wished. Clearly, one of the things it does is make a great archaeologist.

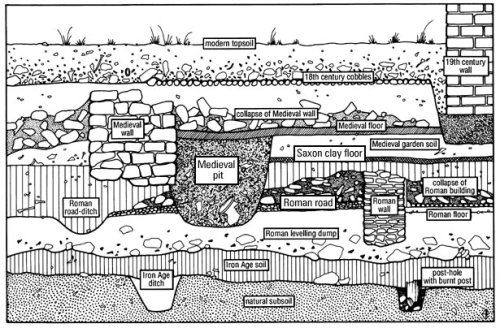

Shortly after her graduation, Kenyon became the official photographer for an expedition to the lost city of Great Zimbabwe, under the tutelage of Gertrude Caton–Thompson, a pioneer for the many active women in the field of archaeology. [Note: There were quite a few women who worked in this field, even as early as the 19th century; not to mention of number of married couples.] Kenyon continued her work in other locales, from early Roman sites in Great Britain to those in Samaria, in what was then British-controlled Palestine. It was in this latter site that she learned the benefit of what is now called stratigraphic sequencing, which is simply digging a trench in a likely place to reveal the events that have occurred over the course of time, mainly through analysis of soil, mineral composition, and the really cool pots, tools, and other human-made items that turn up. This practice would eventually lead to her greatest discovery.

Did anyone find my car keys?

In the 1930's, along with a number of other British archaeologists, Kenyon founded the Institute of Archaeology at the University of London, an organization that sought to organize, and normalize, archaeological work throughout the world and ensure that the next generation of diggers and squints would follow proper scientific practices. During this decade she also continued work on early Roman-British sites, work that was interrupted by the Second World War.

After the war, and her service as a Divisional Commander of the British Red Cross, Kenyon went to work, now as the director of the Institute of Archaeology, to re-establish all of the arcane expeditions that had been on hold during the six years of war. She was not yet forty-years-old.

Kenyon using her x-ray specs on some pot shards; I think ready to use that formidable cane on a disappointing student's skull.

In 1951, she began work on what would be the defining expedition of her career, and the one that brought attention to her style of "digging". The earliest incarnation of the Israeli government gave Kenyon and her crew permission to dig in the West Bank in the area of the Biblical city of Jericho. At the time, much was unknown about the early city and its fabled wall that "came tumblin' down", and it was a site that was particularly favored by stratigraphic analysis. In so doing, Kenyon altered notions of what neo-lithic life was like, not to mention discovering things that were inconsistent with the Biblical narrative.

It's interesting that in our contemporary age, mostly due to the non-theism that has been institutionalized in higher education, it is difficult to gain funding for archaeological work on Biblical sites unless there is a sure chance that it will disprove Biblical accounts or otherwise undermine the belief of the literalist Christian or Jew, as they are often seen in secular political opposition to faculty members. In Kenyon's day, it was the opposite. In general, the taste in universities was much more Christo-centric and, hence, when Kenyon discovered evidence that contradicted the Biblical account of the siege and storming of Jericho by Joshua and the Israelites, she did receive some pressure to "re-evaluate" her data. In the name of intellectual purity, and to her credit, she didn't.

The following is from a site for school-children [which makes it perfect for me] so, while written simplistically, it summarizes Kenyon's finds admirably:

As Kenyon and her team dug down into the mound they made some discoveries that awed archaeologists the world over. It seemed that there had existed a productive well-built city, with massive walls dating from 7000 - 5000 BC, as well as a village community that housed a religious shrine and facilities used for grain storage. What this in fact meant was there had been people living a settled life in the Neolithic Period, 3000 years before pottery was invented. Needless to say, this new discovery completely contradicted the old theories and previously held ideas about the development of pottery.

Kenyon and her team also uncovered massive walls, although they were not the walls Joshua encountered. They were in fact far older. Some parts of the walls had even been built as early as 7000 - 5000 BC. The actual construction of these massive fortifications was truly amazing because they had been built by people that lived 3000 years before the use of pottery, and without the aid of metal tools.

Kenyon and her team also uncovered skulls dated around 6000 BC. The skulls had the flesh removed and cowry shells inserted into the eye's sockets. The features of the skulls had been moulded in plaster. From these skulls as well as bones found on the site, archaeologists have been able to deduce that the first main inhabitants of Jericho had been small-boned, 150cm tall, with long skulls and delicate features. This would not have been possible if not for Kenyon and her excavations at Jericho.

Remains of houses found by Kenyon and her team showed that they had comprised of a dome-like structure made from wattle and daub, and then later, rectangular mud-brick houses. There were no roads or streets among these houses, people communicated through open courtyards.

Remains of equipment included finely carved limestone bowls and polished stone querns. Although no pottery was found it seemed that flint was widely used and flint javelins, arrowheads, hoes and sickle blades were among the remains. The stone querns used for storage of cereals pointed to the harvesting of crops, possibly wheat and barley. It seemed that these early inhabitants also hunted gazelle, identified by animal bones found on the site.

It doesn't look like much now, but you should have seen it in its heyday.

Kenyon became the most famous archaeologist in her field, as she accomplished that which has been the goal of every worker in the arcane since before her and, certainly, after her, as she dramatically and incontrovertibly re-defined our understanding of the past. Every single textbook that covered the Neo-Lithic age had to be re-written because of this stout Englishwoman and her deliberate, painstaking style of field archaeology. She also served as an inspiration to the next generations of archaeologists and anthropologists and as the voice of caution to those who think that we are ever complete in our knowledge of the past. There is, and always will be, more left to discover.

Kathleen Kenyon died in 1978 at the age of 72, spending her final few years in solitude in a remote Welsh cottage, editing her manuscripts.

For those interested in further reading, I would recommend:

Archaeology in the Holy Land, by Kathleen Kenyon

Royal Cities of the Old Testament, also by KK [and my personal favorite]

and

Dame Kathleen Kenyon: Digging Up the Holy Land by Miriam C. Davis