"Who ever met him grieving and failed to go away rejoicing?"

It seems difficult to believe from the viewpoint of the 21st century, in a nation such as ours, rich beyond the ancient world's measure and with freedoms that never would have been dreamt of in prior generations, that, once upon a time, to become a Christian meant to become a kind of monastic. Nowadays, of course, one may transit from heathen to Christian, and vice versa, without any apparent alteration to one's life. The job stays the same, family membership is un-threatened, one's income and possessions are not surrendered.

Such was not the case in the 4th century. Becoming a Christian wasn't so much a "lifestyle choice" but a total and complete commitment to something far greater than one's life. Early Christians would sometimes lose their families, their roles in society, their possessions would happily be given over to their faith community. [Remember that next time we hand out pledge cards.] Their lives would become dedicated to God in a manner that would be found worthy of an intervention in contemporary times.

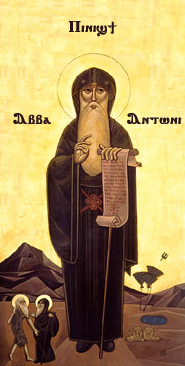

In the midst of this zealous Christianity, Antony of the Desert was its most ardent practitioner.

"Most of what is known about Saint Anthony comes from the Life of Anthony. Written in Greek around 360 by Athanasius of Alexandria, it depicts Anthony as an illiterate and holy man who through his existence in a primordial landscape has an absolute connection to the divine truth....

This "absolute connection" served, through Antony's private and public practices, as the foundation for monasticism and what is known as "ascetical theology".

It was a common practice at this time for fervent Christians to lead retired lives in penance and contemplation on the outskirts of towns, and in the desert, while others practiced their austerities without withdrawing from their fellow men. In even earlier times we hear of these ascetics. Origen, about 249, wrote that they abstained from flesh, as the disciples of Pythagoras did. Antony lived in his tomb near Coma until about 285. Then, at the age of thirty-five, he set out into the empty desert, crossed the eastern branch of the Nile, and took up his abode in the ruins of an old castle on the top of a mountain. There he lived for almost twenty years, rarely seeing any man except the one who brought him food every six months.

In his fifty-fifth year he came down from his mountain retreat and founded his first monastery, not far from Aphroditopolis. It consisted of scattered cells, each inhabited by a solitary monk; some of the later settlements may have been arranged on more of a community plan. Antony did not stay with any of his foundations long, but visited them all from time to time. These interruptions to his solitude, involving as they did some management of the affairs of others, tended to disturb him. We are told of a temptation to despair, which he overcame by prayer and hard manual labor. Notwithstanding his stringent self-discipline, he always maintained that perfection consisted not in mortification of the flesh but in love of God. He taught his monks to have eternity always present to their minds and to perform every act with all the fervor of their souls, as if it were to be their last.

Heathen philosophers who disputed with Antony were amazed both at his modesty and at his wisdom. When asked how he could spend his life in solitude without the companionship of books, he replied that nature was his great book. When they criticized his ignorance, he simply asked which was the better, good sense or book learning, and which produced the other. They answered, "Good sense." "Then," said Antony, "it is sufficient of itself." His pagan visitors usually wanted to know the reasons for his faith in Christ. He told them that they degraded their gods by ascribing to them the worst of human passions, whereas the ignominy of the cross, followed by Christ's triumphant Resurrection, was a supreme demonstration of His infinite goodness, to say nothing of His miracles of healing and raising the dead. The Christian's faith in his Almighty God and His works was a more satisfactory basis for religion than the empty sophistries of the Greeks. Antony carried on his discussions with the Greeks through an interpreter. His biographer Athanasius tells us that in spite of his solitary life, "he did not seem to others morose or unapproachable, but met them with a most engaging and friendly air." He writes that no one in trouble ever visited Antony without going away comforted.

O God, by your Holy Spirit you enabled your servant Antony to withstand the temptations of the world, the flesh, and the devil: Give us grace, with pure hearts and minds, to follow you, the only God; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.